It’s the economy stupid

Julian Matthews, Founder Chairman of TOFTigers, explains why the economies behind tigers, or what he calls ‘Tigernomics’, that play a critical, yet a largely unrecognised role in India’s conservation efforts.

Economies are the real driving force behind conservation today.

Two contrasting issues that were in news last month help to highlight this point. The first that the Kawal Tiger Reserve in Telangana, a park nobody has ever heard of and few care about, had lost its only remaining tiger to poaching. The other article was the exact opposite. Many tiger parks, all of which I knew well, have visited often and have thriving rural economies, were now full of tigers and the authorities could not cope with any more Panthera tigris.

So why this extraordinary difference between tiger reserves? They do, after all, have the same rules and regulations, government funds and charity dollars that 45 years of tiger conservation have thrown at them.

I believe it’s largely a question of economics. You could call it ‘conservation dependent’ economics – but I call it ‘Tigernomics’.

Nature-focused Tourism

The principles of economies work for conservation – helping to value product and services and now, thankfully, are increasingly being applied to nature’s hidden products and resources too. The reality is that free water, clean air and warm sunshine – our natural capital – sadly doesn’t pay the day to day bills in today’s world. A local villager living beside a river that borders a rich biodiverse forest, cannot exchange the water that flows past his house, the clean air he breathes and the warm sunshine on his back to ensure daily food. He still has to cut down the trees for fuel, make new fields from the clearance and graze his cows in the forest peripheries.

As a society, therefore, we should look far more cleverly at the opportunity to use this very same economic system to save our own planet from the wholesale destruction it is facing. Turn ‘nature’ – all too often seen as free and by this reckoning, valueless to humankind – into something that is invaluable.

Yes, this does sound like a dangerous paradox – but this economy is already working wonders in parts of India and Nepal, (and across the globe) using the one creature society does seem to value beyond any real logical reasoning – the tiger. We’re now creating valuable rural economies out of the huge industry of watching – rather than hunting – these beautiful wild cats.

Nature-focused tourism is a huge economy around the globe, the largest per-dollar job creator in the world. A WWF backed report in 2015 states that visits to the world’s Protected Areas is a $650 billion dollar a year industry. It’s already here in India but is still in its infancy relative to its vast potential. It is already paying the bills for tens of thousands of villagers living besides tiger forests – though obviously not all tiger sanctuaries.

I believe the advent of the nature tourism economy has been the saviour of the tiger, more, probably, than any single intervention since Project Tiger was conceived. The late Dian Fossey, a great primatologist, did not foresee the power of her own research subjects (mountain gorillas) to draw visitors to an unknown part of Africa, and thereby save them from what she saw was inevitable extinction from poaching and habitat loss. Likewise, the majority of tiger range countries (13 of them) have lost or are close to losing their wild tiger populations, having never had a viable ‘nature friendly’ economy. Only Nepal, India, Bhutan and Far East Russia have bucked this downward trend in tiger numbers.

Is it worth saving tigers?

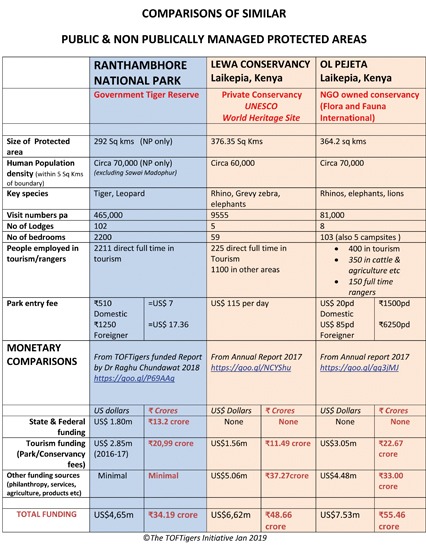

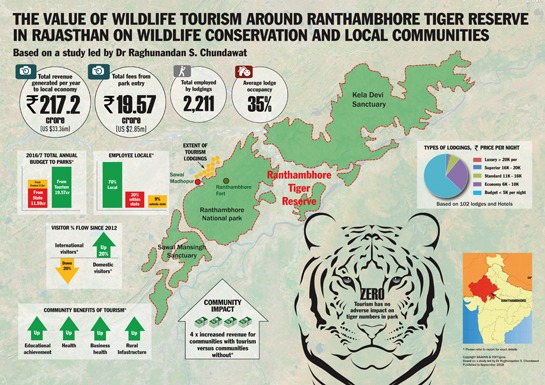

Visitors pay handsomely to see the mystical cat in its mythical land. Many return home to friends and family to advocate passionately for their long term protection, becoming lifelong ambassadors for nature. Furthermore, safari goers make authorities and protectors accountable for what lives in these wild landscapes day in day out. Their interests fund the building of an economy that generates rural jobs, new livelihoods and sustenance that make a landscape and its creatures worth preserving, economically and intrinsically. No other business does this quite so well, or quite so effectively. My organisation, TOFTigers, in 2010, calculated that a single tigress the Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve generated an astonishing US $101 million to the local economy in visitor fees and revenues over the decade of her rule. Now no government can say it’s not worth saving tigers – they simply cannot afford not to invest in habitat protection and long-term conservation.

Visitors, so often disparaged in the media, should be feted as tiger’s saviours. They put their hard earned money, their precious time and often their voices into ensuring parks and wild places remain for future generations. Their visits breed the wildlife advocates, scientists, foresters and conservationists of the future. Their interest turns local communities from conservation victims into wildlife beneficiaries and nature’s stakeholders, more than any other economy can. Harness and educate visitors rather than castigate and exclude them.

The evidence is overwhelming. The well-known tiger reserves like Corbett, Nagarahole, Ranthambhore, Kanha, Pench and Bandhavgarh – those most well visited, having thriving tiger populations. The government’s own Wildlife Institute of India researchers now say many are ‘overfull’. Many parks have been brought back from the brink of collapse, only a decade or more ago, a time in which the growth of this new and dynamic rural economy has boomed. Domestic visitors too have flocked to enjoy these sanctuaries’ extraordinary offerings. However, other parks remain in the conservation doldrums, like Kawal, as are many others that are struggling to save their remaining tigers. The reason? There is simply no new rural economy – that critical ‘behavioural change mechanism’ – that can restructure a Protected Area’s future from one of extraction, overgrazing and marginal livelihoods – to one of protection, alternative livelihoods, new horizons and viable opportunity for thousands of marginalised villagers that border (and live within) these parks and wildernesses across South Asia.

The reality is that it’s not until excited visitors and politicians start to see tigers (and an abundance of other creatures) that anyone becomes excited about a park’s future, and sees the opportunities and monies that are possible to make from it. Good old capitalism at work. Park visitors are effectively the ‘dry wood that furnaces the conservation flames’.

Today the Madhya Pradesh park management not only have state and central funds every year of INR39.7 crore for protection and community support, but a further INR19.4 crore, or an extra 33 per cent funds from visitor park fees to help too. Furthermore, a rural tourism economy worth INR166 crore, with 2,525 new full-time jobs (and probably treble that in ancillary jobs and services) dependent on their Protected Area and its wild inhabitants remaining alive. That’s a lot of revenue, and Government tax off the back of it, that was not there just 20 years ago.

Do the perils of tourism make it worth the risks?

So, if this is such a brilliant idea for saving India’s parks – and the domestic demand is there – why hasn’t it happened across India’s Protected Area network and why is the Kawal Tiger Reserve still where the Pench Tiger Reserve was 20 years ago?

The authorities’ blinkered approach to this ‘economy’ manifested itself in 2012 when an activist ‘accused tourism of killing tigers’ in the Delhi Central Court and the parks were closed for four months. The National Tiger Conservation Authority’s cohorts, far from defending the right of citizens to visit and enjoy their own natural heritage, (as their own project mission prescribes), decided instead that this ‘evil scourge’ should be bottled up in 20 per cent of a tiger reserve’s natural landscape. As a result the real value of ecotourism to local communities and parks has not been allowed to fully manifest.

Visitors are a nuisance to many forest authorities, but really the problem is not the visitor per se. The problem is the complete lack of planning and investment for rural economies that exist in the shadow of all our Protected Areas. Nature-based tourism is a business like any other and needs the same forward planning, infrastructure investment, expertise and regulation as any other enterprise, to ensure its visitors experiences and long-term sustainability. Particularly if we wish to make certain that local communities become the primary beneficiaries of high-value, low-impact tourism.

Basically, we need smart forest planning, which replicates the processes and land use planning of the smart cities people aspire to create.

This is not a problem solely faced by India. It’s no different in any Protected Area across the world. Well thought out policies that benefit wildlife protection, ensure better visitor experiences and catalyse opportunities to benefit local communities. But, thus far, for any potential investor or visitor, ecotourism in India has been more about what you can’t do – than what could be done, or what needs to be done.

The World Economic Forum’s 2017 Travel and Tourism report states that even though India is ranked as one of the world’s top biodiversity hotspots, its ability to draw visitors to its remarkable natural heritage is a dismal 113th in the world, not helped by the Government’s prioritisation of its merits and expenditure on this sector at a similar lowly position – below Mongolia and Tajikistan. Lastly and more worryingly, the environmental sustainability of this sector ranks almost last in the world at 134 of 136 countries.

Planning the future

Allowing a variety of public-private partnerships and community conservancies with new funding mechanisms on poorly protected landscapes and marginal farmlands will be critical to the future. Homestays are working wonders with snow leopards in Ladakh and Sikkim, and new initiatives are being undertaken in Gothangaon village (see page 41), outside the Umred, Paoni-Karhandla Wildlife Sanctuary by the Sanctuary Nature Foundation and a private partner invited by the community to help restore and rewild their own land holdings. Such examples of new management regimes, with innovative funding mechanisms and world class visitor experiences must be at the forefront of the change.

Allowing a proven conservation-dependent economy to eclipse a host of far more dangerous extractive economies that would kill the tigers and its wild lands irreversibly, is not just an economic and moral imperative – it’s a planetary necessity.

Author: Julian Matthews, First published in: Sanctuary Asia, Volume XXXIX Issue 4, April 2019